What’s your view on customers’ value to innovation?

July 27, 2012 6 Comments

More and more, customer-centricity is becoming a thing. As in, an increasingly important philosophy to companies in managing day-to-day and even longer term planning. In comes in different forms: design thinking, social CRM, service-dominant logic, value co-creation.

But it’s not pervasive at this point. Companies still are spotty on how much they integrate customers into their processes. This is a revolution that will take some time to unfold.

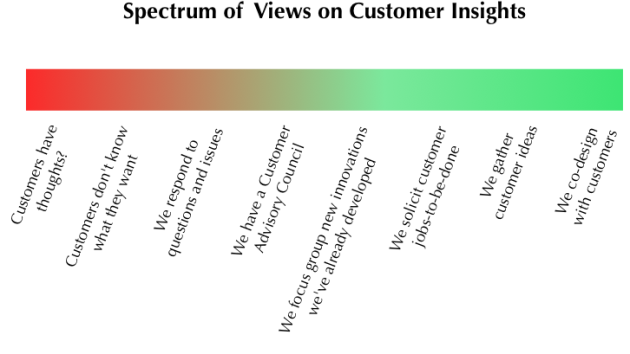

In terms of innovation and product or service development, there is a spectrum of where organizations are today:

Quick descriptions of each point on the spectrum…

Customers have thoughts?: For these firms, customers are transactions. How will I know if I’m attuned to the customer? I look at my daily sales receipts. If they’re up, I’m attuned. If they’re down, I’m not!

Customers don’t know what they want: What was it Steve Jobs said again? Ah, yes: “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Unlike the previous point on the spectrum, here, companies have considered that their customers have thoughts. They just don’t think there’s much point in paying attention to them. In a more charitable vein, Roberto Verganti cites companies that “make proposals to people”. While there’s no direct customer engagement, these companies build product intuition through trends changing other sectors. Unfortunately, many companies with the “customers don’t know” aren’t actually doing that either. It’s more someone’s whim defining the offering.

We respond to questions and issues: In this part of the spectrum, companies may proudly say they listen to their customers. Not too deeply though. It’s more a surface-level valuation of customer input. It doesn’t fundamentally change the company culture, or really draw customer insights more deeply into the organizational workings. The hip companies have extended this work out into social media. They monitor tweets, Facebook posts, Pinterest pins, etc. for complaints, questions and sentiment analysis.

We have a Customer Advisory Council: Take some of your best customers, and appoint them to a special panel that meets periodically during the year. Good forum for airing bigger picture issues. In this case, companies asttempt to more directly solicit customer input into their thinking. These sessions are good, because otherwise the only way customer feedback gets into an organization is during the sales process and then one-on-one with an account/customer rep. Insight gets trapped in a CRM account somewhere. While progressing on being attuned to customer insight, CACs are still siloed affairs. Many in the company have no idea what comes out of them. And they are removed from the day-to-day work that truly defines an organization.

We focus group new innovations we’ve already developed: As opposed to developing something and putting it out there, these companies work with focus groups to understand what is liked or disliked about an offering they have developed. This can be quite valuable done right, and becomes a direct conduit for customer insight into the company. The biggest problem here is that it’s after-the-fact: the product or service has already been designed. Now, in the lean startup methodology, this approach of develop and test is a core principle. In corporate land, focus groups may be less about test-and-learn, and more about affirming one’s pre-held views.

We solicit customer jobs-to-be-done: As part of their planning and design process, companies solicit customers’ jobs-to-be-done. They want to get a bead on customers are trying to accomplish with their products and services. This is no small feat. I’ve done this work myself, and it does take a willingness to open one’s mind beyond your own personal beliefs. But getting and using jobs-to-be-done in product and service design is a basis for better, more valued offerings to the market. Key here is not just engaging customers on their jobs, but actually incorporating that into design.

We gather customer ideas: Customers are using your offerings, and can see opportunities where new features and services would help them. While certainly product, R&D and marketing will come up with ideas on their own, what about the people who actually use your products? This is a form of open innovation. The amount of ingenuity outside your company walls dwarfs what you have internally. Key here is to solicit around focused areas for development, which makes using the ideas more feasible inside companies. Wide open idea sites can be harder for companies to process, as they don’t fit an existing initiative. Defined projects have a receptive audience and a commitment to progress forward.

We co-design with customers: The most advanced form of customer-centricity. Customers have a seat at the table in the actual development of products and services. This is, frankly, pretty radical. Their input guides the development, their objections can remove a pet feature favored by an executive. This is hard to pull off, as it is counter to the reason you have employees in the first place (“experts on the offering”). It requires a mentality change from being the primary source of thought to a coordinator and curator. Key here is deciding which customers to involve at what point in the process.

My guess is that most companies are still toward the left side of the spectrum, but as I say, it is a changing business world.

I’m @bhc3 on Twitter.

Good post, Hutch. I’ve been thinking about this issue recently too.

My take on this:

I agree with you that firms need to put the customer in the center of their activities – particularly when it comes to innovation. Eventually, it’s the customer determining adoption and therefore innovation success.

However, customer involvement and the way of putting customer value in the center differs along the innovation spectrum.

Innovation in existing markets often refers to improvement or enhancement of exisitng offerings. It covers debugging, adding new features, launching new versions etc. These innovations can be well based on customer research and co-created as the already existing offering as the frame of reference is not left.

When it comes to entirely novel offerings through more radical innovation, often related to new market creation, customer involvement needs to be different. A “customer knowledge chasm” exists, as average customers tend to stick to existing frames of reference and have major difficulties in conceiving of novel frames that do not yet exist. That’s why Verganti suggests that entirely new solutions are “proposals” from the innovator to the market that need to become validated. Of course these proposals need to address (unmet) customer needs or jobs-to-be-done and must not be developed in a “vacuum”. Involvement of selected edge customers (e.g. lead or creative customers) is likely to help bridge the chasm to the mass market.

I think the role of customers shifts from providing solution requirements and specifications to validating proposals as we move along the innovation continuum from incremental towards radical and disruptive innovation. Across the entire continuum, however, innovative solutions need to be build around customer needs. The more radical the innovation, the more experimental and emergent the approach.

Good take on the spectrum Ralph. You’ve outlined a couple here. There’s the level of innovation we’re talking (small incremental to radical). And the point in the innovation development process where a company is.

The Verganti sense is particularly apt for radical innovations. But even less ambitious efforts to bring significant advances to existing experiences benefit from Verganti “make a proposal” type of thinking. In fact, a number of examples in his book were of that variety.

Overall, you could almost look at the spectrum as a vaguely left-to-right flow of developing innovations. It wasn’t built to serve that purpose. It was more a statement of how much companies “invite customers in” to their processes. But if you bypass some parts of the spectrum here and there, you can see how elements apply to an innovation flow.

A flow that better describes what you’re outlined here would be a good idea though.

That’s an interesting thought, Hutch – this rough left-to-right flow sounds reasonable.

I just came across a reference, summarizing well my point above:

“The danger in user-centered design is that it releases the designer of the responsibility for having a vision for the world. Why have one when we can just ask users what they want? But this is a very limiting mindset. The user sees the world as it is. Our job as builders is to create the world as it could be.”

While incremental innovation is more like optimizing the “world as is”, radical innovation seems to be more about building the world as it could be. In both cases, people’s needs are addressed but way and intensity of customer involvement is different.

Very much agree here. Firms are still the ones that must own the proposals and the determination of where they want to go in the market. I get the sense from some critics (“Steve Jobs said customers don’t know what they want”) that talk of customer involvement in product/service innovation is tantamount to handing the roadmap keys over to customers. It’s an abdication of one’s growth responsibilities. A death sentence of product mediocrity. Not the case at all. Rather, customer insight is an enriching source of information. Different insights, as you mentioned earlier, can be incorporated at different parts of the process.

What’s new in customer-centricity is to advocate for the increased usage of these insights in the process. At least in my B2B experience, customers are itching to be more deeply involved. And product managers would readily accept greater engagement with customers as they flow through the conception, design and development of radical, major or incremental initiatives. I’ll assume B2C customers, at least in many sectors, would similarly be interested in being more involved.

Great piece Hutch, as always.

There is clearly a huge chasm between focus groups and opening up the doors of innovation to customers in a systematic and strategic way. It would be great to follow up on Ralph’s comment adding the kind of roles, actions and approach expected both from the organization and the customer at each stage.

As a final thought, I’m not sure about the order and completeness of the last 3 more customer centric steps. Most companies, even those already attuned to innovation management, aren’t very well versed in outcome driven innovation and jobs to be done. That’s why co-creation and bottom-up participation aren’t always directed to the right goals and end up adding rear looking noise instead of building future competitive differentiation. Also isn’t co-creation a deeper but less scalable approach compared to crowdsourcing and thus its place in the continuum logically before innovation management?

On the other side I suspect there may be some additional aspects worth to be considered such as: research communities (much better than focus group) during the product design and not after it, the engagement of employees to weight and refine customers’ ideas, etc.

For sure, the right side of the spectrum is mostly untested ground. No, companies aren’t well established there.

I put co-creation to the right of idea solicitation because it’s easier for companies to collect ideas than to act on them. Co-creation is a more active engagement with customers. The spectrum wasn’t attempting to plumb levels of scalability as much as it was to define the depth of customer involvement in internal processes.

Good points on research communities. I guess the closest “accessible” things companies might have today are user forums, really. And yes, employees are quite valuable! I just kept the focus here on customer involvement.