Using Open Innovation to Be Competitively Unpredictable

November 22, 2010 3 Comments

During a Twitter Q&A organized by open innovation thought leader Stefan Lindegaard, Psion Teklogix CEO John Conoley posted this:

http://twitter.com/#!/johnCEOatPsion/status/22796327966

How interesting is that? Using open innovation to be “competitively unpredictable”. I love that concept. Let’s understand where John is coming from.

[tweetmeme source=”bhc3″]

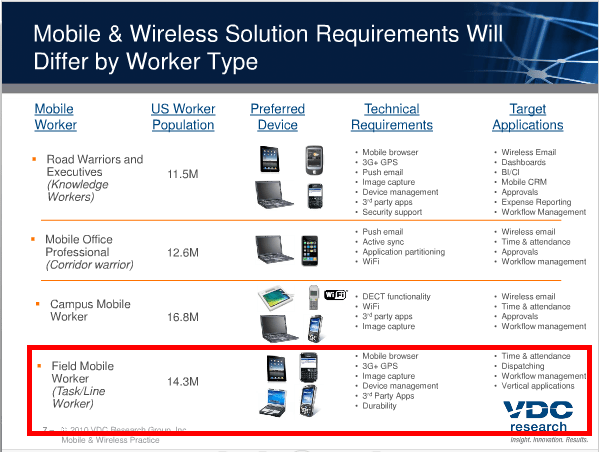

First, have you heard of Psion Teklogix? They make “rugged mobile computers”. Think Blackberry or iPhone, but industrial strength with specialized purposes, hardware, and made to withstand punishment. From an enterprise perspective, the chart below by VDC Research provides some perspective on mobile computing for work. I’ve outlined in red the section where Psion operates:

Psion’s computers are used in a variety of industries for inventory tracking, couriers, field service and other demanding jobs. The company is #3 in its industry (Motorola occupies the top spot). A key part of Psion’s strategy is to make its rugged mobile computers modular and customizable. This customization allows them to be adapted to different uses. Building on this modular and customization philosophy, the company has developed an ecosystem of third party vendors who make components that plug in with Psion’s products.

I had a chance to talk with Todd Boone, Director of Market Development for Psion. He described the company’s open innovation efforts.

Pace of Change in Mobile Has Accelerated

Before talking about open innovation, first understand this. Todd Boone noted that the pace of change of mobile computing has accelerated in the past several years. Anyone tracking the space probably gets that intuitively. This means is that the uses of mobile, the emergence of new competitors and the changes in technology change more frequently. As an example, on the consumer side, how long have Apple and Android been so influential in the mobile sector?

Indeed, VDC Research noted the changing dynamics of the rugged mobile computing market in a recent article:

Another critical challenge facing rugged handheld vendors is the increasing level of competition from smartphones and other emerging devices – especially for field mobility applications. While smartphones do not have the same level of integrated I/O capabilities nor the level of ruggedness offered by rugged handheld devices, their proliferation in the enterprise (and lower adoption cost) are making them target devices to support more sophisticated enterprise applications. Plus, in the field mobility market the rugged handheld community is most challenged from an OS perspective. Although there is a strong application and developer community supporting field mobility applications on Windows Mobile devices, customer expectations in terms of user interface and experience – especially for field mobility applications – is increasingly influenced by consumer oriented smartphones.

For companies operating in the mobile space, such dynamics make it harder to “know” everything, and to have the resources to respond accordingly. Nimbleness and flexibility are needed to address the unpredictable course the mobile sector takes.

As Todd Boone explained to me, Psion needed a strategy that leveraged their modular platform strategy while recognizing they can’t realistically know all the emerging use cases and technologies out there.

Answer? Open innovation.

Ingenuity Working

On March 4, 2010, Psion launched Ingenuity Working (IW), a site built to expand its open innovation activities. Psion CEO John Conoley described its mission this way:

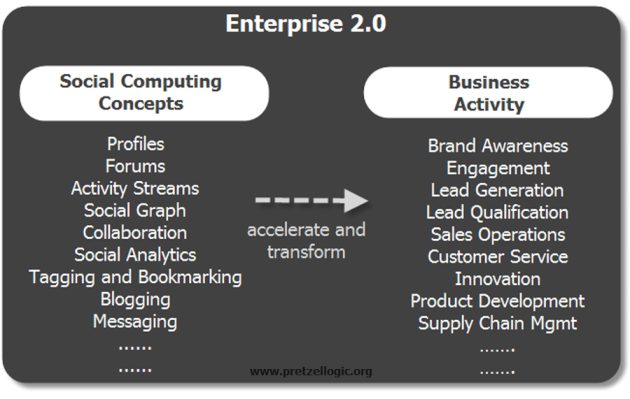

The open, online community in Ingenuity Working brings us closer to our customers and their thoughts and will allow us to socialise and commercialise innovation. We are using social media to bring our developers and resellers together with our customers, all over the world. Essentially, everyone will be putting their heads together to help create technology that best fits a company’s individual requirements – that has to be a good thing.

In talking with Todd, I learned that the initial thrust of the IW community is focused on partner vendors, rather than direct feedback from end-user customers. In some ways, this is similar to P&G’s open innovation approach.

Engagement with external parties occurs via discussion forums, blogs and a “secure zone” for each partner. In these arenas, there is a two-way exchange of product ideas and use cases. An example can be seen in the section of IW devoted to discussions for developers of Windows/CE/WM/Embedded.

Now that’s some esoteric stuff there. But here’s the thing. It’s groundbreaking in the rugged mobile computing industry to have this all ‘hanging out there’. It becomes free research for competitors too, in a way. Which one may view as a risk of this whole endeavor,

Here’s how Todd describes the Psion open innovation vision:

Rather, we think it’s the opportunity to drive the market to a new reality. A market that drives itself in a way that is inherently beneficial to customers and partners alike based on the real-time, open dialogue that starts prior to any development activities taking place and continues through to product maturity. Real success will come, I think, when marketing and engineering no longer make product decisions but rather our community of customers, partners and developers does.

Psion is early in its open innovation initiative, and plans to improve and evolve its program. The company is engaging partners on hardware, software, standards and a wide variety of use cases. These efforts complement its existing offline channels and research.

Becoming Competitively Unpredictable

Finally, that great quote from Psion’s CEO about embracing open innovation to be competitively unpredictable. I asked Todd for a bit more context. What exactly does that mean?

He noted that typically, large companies describe their roadmap for the next several quarters or years in terms of product development. The challenge with that approach is that it’s company-centric, and its effectiveness is limited by the increasing rate of change in the industry.

The other dynamic is Psion’s orientation toward creating an open platform that can be configured for different uses. This platform philosophy is a core strategy.

So by engaging with external parties, Psion is looking to (i) stay on top of emerging market changes; and (ii) leverage this large collective intelligence to develop applications and hardware for its configurable platform.

Ideas which would be hard to forecast out over the next 6, 12 or 24 months. If you’re a competitor, this makes it harder to know what Psion will do.

In other words, they become competitively unpredictable.

[tweetmeme source=”bhc3″]

Well, this is pretty cool. I’m pleased to announce that

Well, this is pretty cool. I’m pleased to announce that

The Conversation